Aligning Reading and Writing Instruction in Kindergarten to Grade 2

K-2 teachers are tasked with teaching children the foundational skills that enable them to flourish as readers and writers. The developmental range, as we all well know, is wide, so the need to differentiate instruction is paramount. I liken it to a rollercoaster ride; with learners’ readiness at all different altitudes— and their progress in constant motion—teaching needs to be both highly responsive and highly intentional. From teaching concepts of print to developing comprehension, from planning lessons for small group instruction to word study, from modeling letter formation to story writing, teachers in these early grades have a great deal to keep on track. It’s exciting, rewarding—and overwhelming.

“Just work smarter,” my principal would say when I’d express concern that despite my hard work, students weren’t progressing far enough.

I would leave his office bemused. Work smarter? I didn’t understand how to do that. It would take me years to figure it out. I’d like to spare you years of trial and error and feeling overwhelmed. So in this article, I'll provide concrete advice on how to actually work smarter.

Spoiler alert: The main strategy is to align your reading and writing curriculum.

Work Smarter

Aligning your reading and writing curriculum helps you use your time more efficiently, and it also deepens students’ understanding of what they are learning. Why? Because reading and writing are reciprocal processes, so it makes sense to children when we present them as two sides of the same coin. By contrast, when we design lessons and curriculum that unnaturally keep them as separate endeavors, it makes it tougher for students to develop strong literacy foundations.

To synch up reading and writing instruction, it’s helpful to focus on the following four areas:

- Align Tools

- Align Instructional Practices

- Align Methods for Supported Practice

- Make Word Study a Foundational Piece

These few considerations will help plan your curriculum—and your classroom environment—in ways I wished I had understood earlier in my teaching career.

Align Tools

Selecting, using, and offering students the right tools and material at the right time is both a science and an art. Before we fill the book tubs, the library, the messages for interactive writing, we have to commit to a clear model of what literacy learning involves. Doing so helps us from dashing every which way, trying to teach everything in a scattershot manner. Adria Klein during her keynote at the 2020 National Reading Recovery Conference said this:

“Literacy is complex and dynamic. Teachers make minute-by-minute decisions and all of these decisions are dependent upon who our students are—their current situations, their experiences, and how all of this changes over time.”

Adria’s words inspired me to answer the question. How do I help teachers teach reading and writing in a manner that is manageable, yet responds to the dynamic changes that students present day-to-day? For me, part of the answer was to offer teachers reading and writing tools that help them simplify complex processes for themselves, and in turn, for their students.

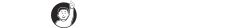

Tool for Reading

My favorite simple reading tool is a graphic recently created by Nell Duke and Kelly Cartwright called the Active View of Reading. As you can see, their active view includes word, recognition, language comprehension, bridging processes, and active self-regulation. This graphic shows teachers exactly what to instruct students on in reading. It’s interesting to notice that some skills such as fluency and vocabulary, overlap in both language comprehension and word recognition, thus aptly called “bridging processes.”

I can’t underscore enough that this tool for reading, and the tool for writing described next, are to be leaned on but not used as the be-all-end-all. What do I mean by that? Just that we educators need to look at any model as having blurred edges, so to speak. For example, Duke and Cartwright include in their graphic that “reading is also impacted by text, task, and sociocultural factors.” In my view, these words are a nod to the reality that the process of reading is always being further researched, defined, and no one model can be fully inclusive.

In addition, as we use any framework, we want to think about the practical application in the classroom. What are the reading and writing practices that make the model function? For example, reading aloud, independent reading, reflecting about reading, writing letters, poems, stories—to name just a few—are the tasks that make the reading and writing process come alive for learners.

Tool for Writing

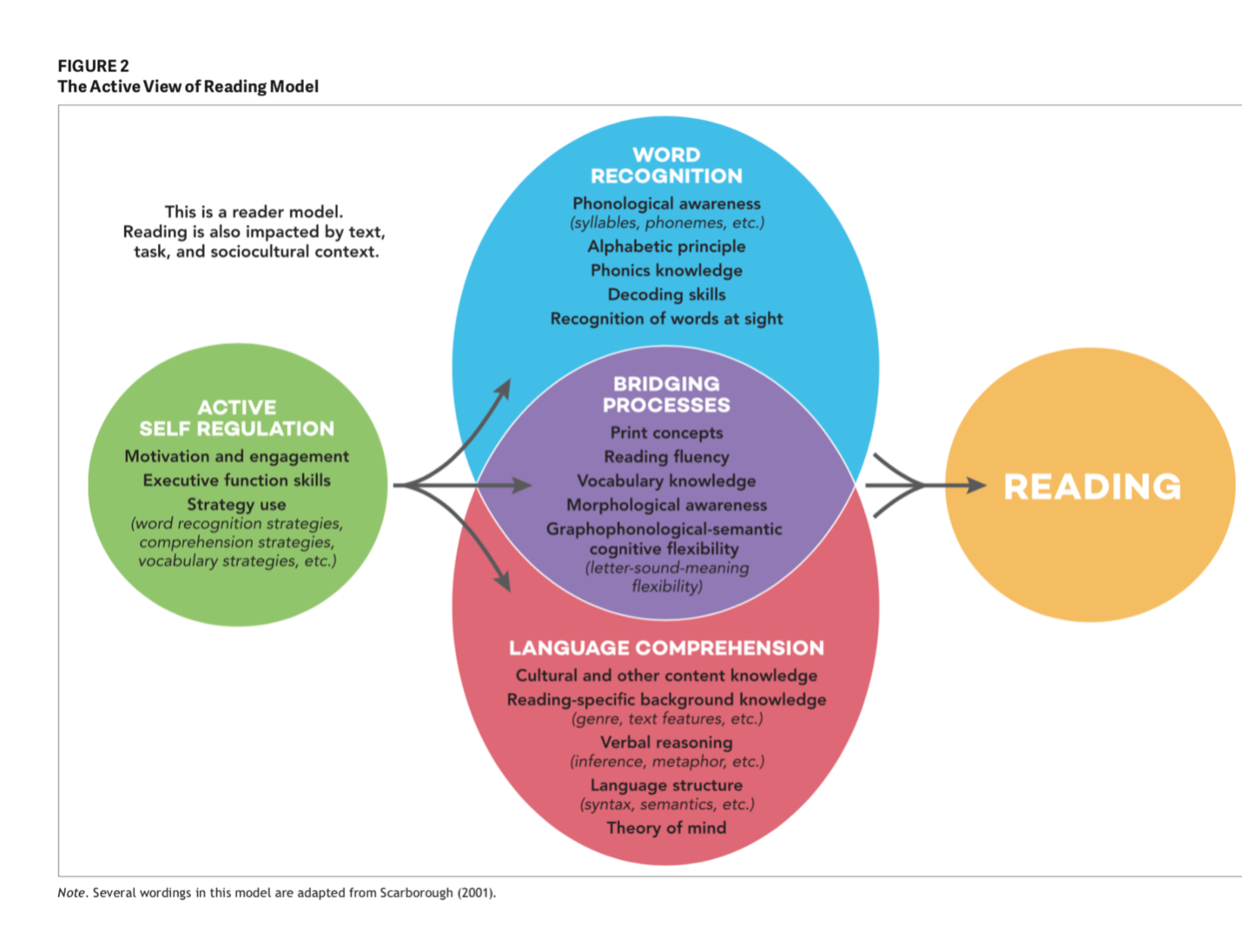

For a simple writing tool, I suggest the “We-Do” model of instruction because it overlaps so well with the Duke/Cartwright reading model. It’s featured in my newest book “We-Do” Writing; Maximining Practice to Develop Independent Writers. The model includes three instructional strands: language composition (similar to language comprehension in the Duke/Cartwright model) language conventions (similar to the word recognition strand in the Duke/Cartwright model) and writing process (similar to the bridging processes in the Duke/Cartwright model).

I purposefully included the instructional practices in the “We-Do” model, so that educators can more easily see what the teaching looks and sounds like. There are three types of instructional sessions—interactive writing, write aloud and writing process. And, anticipating the teacher’s need to differentiate instruction, I named three levels of support—share, guide, apply. This writing tool shows teachers what is vital to instruct students on in writing—and how to make it happen. As you can see, there are many similarities between these two tools. If you place the two graphics side-by-side and use them to help you plan, you will be well on your way to teaching reading and writing more efficiently and effectively in the classroom.

Align Instructional Practices

One vital goal for our younger learners is to be able to read and write words easily and automatically. This happens through a process that David Kilpatrick (2015) and other researchers call orthographic mapping. During this process, children are segmenting and blending the sounds in a word and attaching those sounds to letters. This process essentially glues a spelling to its pronunciation turning a word that was once unfamiliar into a word that can be read and written easily. When children can read and write words easily and automatically, it frees up cognitive space to work on higher levels of composition and comprehension.

In his book, A Fresh Look at Phonics, early reading expert Wiley Blevins says, “It takes most students four to six weeks to get to mastery on each phonics skill.” Because this process takes time and practice, it makes sense to consider instructional practices across reading and writing that will give students repeated practice with orthographic mapping. Doing so will ensure that all students can transfer what they learned to future texts they read and write.

Now, let’s look at two instructional practices that align across reading and writing to assist with orthographic mapping: teaching with decodable texts and Interactive Writing.

Teaching with Decodable Texts

Decodable texts (sometimes referred to as accountable texts) are defined as texts that children can decode based upon what they have already learned during their word study instruction. If during word study, for example, you had been working on the sounds of P, D, E, F, and G) it would be helpful for at least some of the children to read decodable texts that included those letters, as well as other sight words they have learned. Teachers can then coach/instruct students while reading helping them to apply what they have learned in word study.

Engaging in Interactive Writing

Interactive writing is a type of instructional session in which the teacher and students share a pen to write a message. C. C. Bates details this type of collaborative writing in her book entitled, Interactive Writing: Developing Readers Through Writing. In the “We-Do” model of writing, Interactive Writing is used to share the pen just as she detailed in her book, but it’s also a time to apply what has currently been taught during word study/phonics and conventions. Because of this, teachers typically choose what the children will write to ensure that what they write gives them practice with what has been currently taught. If we go back to the reading examples of the children learning the letters f, d, p, e, d during word study, the teacher might write the sentence "I fed a pig." with the children so that they got to practice with the letters and sounds they had been studying during word study. Both decodable texts and a more systematic approach to Interactive Writing give students practice with what they are learning in word study.

When you pair the instructional practice of using decodable texts with a more systematic approach to Interactive Writing, you are setting yourself up for a more efficient and a more effective way of teaching students how to orthographically map a word, thus helping them to read and write at the word level with accuracy and automaticity.

Align Methods of Supported Practice

In both reading and writing instruction, it’s vital to give students the amount of support they need to be successful. Too much support and we rescue them. Too little support and they are frustrated and in a state of confusion. In both reading and writing, I have noticed that teachers (including myself) model for far too long and move children to independence far too quickly. My suggestion is to linger longer in those middle phases when necessary. Those middle phases in both reading and writing are:

- Share: This is often for whole group, when the teachers are doing reading or writing work together.

- Guide: This is often for small group, when a group of students is trying a particular type of reading or writing work while the teacher supports.

- Apply: This is often for one-on-one. With teacher support, students are now integrating what they have learned in reading or writing into new topics/genres and texts.

Some students will need lots of time in the “we-do” phase of instruction to become independent, while others will need significantly less. I suggest that teachers use their formative assessments to carefully plan and craft reading and writing instruction, making decisions about whether they are going to share the work, guide students to try it on their own, or have them apply it to new topics and ideas.

Make Word Study a Foundational Piece

Word study is the essential building block for all reading and writing instruction. Without it, everything falls apart. In the figure below, you see the three brain regions associated with reading. The first two regions are typically intact. The third region, the phonological assembly region of the brain, is the part that connects letters to sounds. Brain scans have shown that this region is not fully assembled and must be built through successful instructional experiences (American Psychological Association, 2014; Hruby & Goswami, 2011; Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2004; Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2008). Word study/phonics is an important way to build this region.

Word study needs a strong presence in both reading and writing instruction. Giving word study more time helps students develop letter-sound connections. Word study/phonics supports children as they learn to encode and decode text. Although some students learn these skills naturally through reading and writing, most do not and need word study to be a part of their instructional day. Rasinski and Zutell (2010) when defining word study said, “Word study is the direct study and exploration of words. It refers to the study of foundational skills such as phonemic awareness, phonics, high-frequency words, spelling, handwriting, and vocabulary."

Let’s examine why this is vital for all students.

- Supports automaticity

A systematic word study/phonics program will not only ensure that all students have the foundational skills they need but that these foundational skills move from being accurate to automatic; therefore, freeing up cognitive space for deeper level composition and comprehension skills. Students achieve automaticity by what David Kilpatrick calls orthographic mapping, which is the process we use to store printed words in our long-term memory.

- Time factors

Research hasn’t determined an exact amount of time of word study instruction per day but researchers such as Nell Duke have suggested about 45 minutes. That sounds like a lot but keep in mind that a majority of word study should be in the practice phase, which can take place during Interactive Writing and while students are reading decodable texts. You can also achieve this recommended amount by embedding word study throughout the content areas—throughout the school day. In other words, it can be delivered as brief separate lessons as well as touched upon within other subject areas.

- Whole class, small group, one-on-one

These sessions may take place with the whole class, as well as with small groups and one-on-one conferences. Nell Duke also notes that different students will need varying amounts of practice. My general rule of thumb is that teachers should be doing around 20–30 minutes a day of whole-class word study instruction/ practice and then giving students who need a more tailored practice in small groups and/or one on one.

Leveraging the power of the reading/writing connection really can make our lives easier and our students stronger. By giving word study a central role, and by aligning your tools, your instruction, and your levels of support, you will be “working smarter” as a teacher. And your students will be working smarter as readers and writers.

References

American Psychological Association, (2014). http://www.apa.org/action/resources/reseach-inaction/reading

Blevins, Wiley (2017). A Fresh Look at Phonics: Common Causes of Failure and 7 Ingredients for Success. Corwin Literacy. Thousand Oaks, CA.

Cartwright, Kelly and Duke, Nell (2021). The Science of Reading Progresses: Communicating Advances Beyond the Simple View of Reading ILA Reading Research Quarterly 0 (0).

Hruby G. G. & Goswami. U (2011). Neuroscience and Reading: A Review for Reading Education Researchers. Reading Research Quarterly, 46(2), 156-172.

Kilpatrick, D. A. (2015). Essentials of Assessing, Preventing and Overcoming Reading Difficulties. John Wiley and Sons.

Klein, Adria (2020). Looking Back and Moving Forward: Literacy Learning in the 21st Century (Keynote presentation) National Reading Recovery and K–6 Literacy Conference, Columbus, Ohio, United States.

McCarrier, A, Pinnell, G & Fountas, I (2000). Interactive Writing: How Language and Literacy Come Together, K-2. Heinemann.

Mermelstein, Leah (2020). “We-Do” Writing; Maximizing Practice to Development Independent Writers. Benchmark Education. New Rochelle, New York.